Just because.

Billy Bragg, "I almost killed you".

This too.

Billy Bragg/Kate Nash. "Foundation/A New England"

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

Concentrating the mind, wonderfully

Almost exactly a year ago, I ended a rather long silent pause here with a post about death.

Although I didn’t feel like mentioning it at the time, I had, in fact, just returned from a two-week stay in the US, where I had witnessed the conclusion of my mother’s battle with lung cancer. Mortality was, as you might imagine, not so much an abstract issue for me at that time.

But as with all terminal illnesses, 'the end' was – by definition – hardly a surprise; in the months leading up to it, I had done a lot of thinking about what was coming. One of the things I reached for was Norbert Elias’s book, The Loneliness of the Dying. I had come to know Elias’s work through my research on the history of violence and crime, and it had come to play an important role in my thinking about the world. I suppose it might strike you as odd to consult a sociological theorist when dealing with a personal sorrow; on the other hand, maybe it is a sign of quality theory that it tells you something useful about real life.

In any case, The Loneliness of the Dying is quite a remarkable little book. It betrays, in parts, Elias’s tendency to express himself in a somewhat dry, sociological language, but there are other insightful and almost poetic passages.

I quoted one last year:

In the brief comments I managed at my mother's funeral, I quoted another passage. ‘Death’, Elias wrote, ‘is a problem of the living. Dead people have no problems.’

My mother was born into a poor-but-respectable family in Stanley Baldwin’s Britain, and she finished school at 14 to go to work, which was typical of a girl in her class and time and place. And despite crossing an ocean and ascending into the relatively comfortable lower reaches of the post-war American middle class, she remained indelibly marked by those origins, which only seemed to emerge more and more during the last decade and a half of her life.

One might think it odd, then, to remember her with words borrowed from an academic, the founder of figurational sociology – and a German no less. (Albeit one who was a victim of the Nazis and eventually became a British citizen.)

However, I was pleased to find that the words I had groped for turned out not merely to be the unfortunate affectation of a son with Too Much Education: in talking to the woman who had supervised my mother’s hospice care, I discovered that Elias’s book – with its condemnation of the ‘veil of unease’ modern society had thrown around death and the resulting isolation of the dying that this caused – had been one of the works that had inspired her to do what she was doing.

And what she and her colleagues were doing was impressive indeed. Like my mother, my father (two decades earlier) had died at home, cared for by my mother with the assistance of hospice.

Watching the relentless approach of his death over 18 months had made a strong impression on my teenage brain, as you might guess. In any case, since I came late in my parents’ lives – they were in their mid-40s when I surprisingly arrived on the scene – this meant that by the time I was in high school many of their friends (the adults I was closest to) were in their 60s or older, and the usual attrition was already well under way. By the time I graduated, I had carried the coffins of some half a dozen people whom I had loved very much.

What I suppose I’m trying to say is that, fairly early on, it had become clear to me that death was a fairly normal part of life.

(I have no wish to exaggerate my experience: obviously, violent death is something I’ve no direct experience of, something that far too many young people in far too many parts of the world have to deal with. I am not comparing myself to them.)

In any case, I had to think about a lot of the above a couple of weeks ago, when I visited a remarkable exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in London.

In ‘Life Before Death’, German photographer Walter Schels offers a powerful meditation on the experiences of dying people. Schels contacted people at hospices and found several who were willing to be photographed shortly before and immediately after their deaths. The result is a series of portraits combined with stories (written by Schels’s partner Beata Lakotta) that – I think – express in a manner that is all too rare the curious mixture of profundity and banality that inheres in the experience of death.

In their low-key way, they manage to pull back the veil, at least a little bit, on the mysteries of the dying.

Joanna Moorhead’s profile of Schels and Lakotta for the Guardian makes clear what an emotional and logistical challenge this kind of project posed. Schels was motivated by his own fears regarding mortality (and his comments about his early life demonstrate that early exposure to death doesn’t necessarily inure one to its terrors). The essay also points out something that echoes Elias’s words that I quoted above:

They both feel altered by their work on the project:

Over the last few years of her life, my mother and I spoke quite openly about death. We had some different views on the matter of the afterlife, but, once acknowledged, that mattered far less than you might think. (As Moorhead observes of Schels, ‘He remains, as he has long been, an agnostic, having noticed that believers and non-believers alike showed the same fear of the unknown that awaited them.’)

Although no stranger to self-dramatisation, she faced her end with a clear-eyed stoicism that was remarkable. Don’t misunderstand: she was terrified. But somehow she managed to exude both calmness and a dark sense of humour almost to the end. And then there followed an awful period in which she could no longer express anything coherently. There were occasional moments of lucidity and recognition in her eyes. What was going on behind them, though, remains a mystery. The peaceful expression that, eventually, marked the end of her struggle is difficult to describe in words. But I believe I recognised it in many of the images that Schels captured.

The exhibit runs to 18 May. For those in London, I recommend that you go. Leave yourself some time. This is not something to rush through. Spend a good long time looking at the faces. And read all of their stories.

It is unsettling and saddening and uncomfortable. But it also generates, in the end, a curious sense of hushed tranquillity. (A similar set of emotions, I note, that accompanied my reading of Jim Crace’s powerful novel, Being Dead. Something, as The Wife has pointed out, that is rather more complicated than 'joy'.)

If you’re not in London, a sample of the images is available.

This has become far longer than I intended, so I'll conclude by leaving the last word to Schels (and by thanking him and Lakotta for their powerful work):

Although I didn’t feel like mentioning it at the time, I had, in fact, just returned from a two-week stay in the US, where I had witnessed the conclusion of my mother’s battle with lung cancer. Mortality was, as you might imagine, not so much an abstract issue for me at that time.

But as with all terminal illnesses, 'the end' was – by definition – hardly a surprise; in the months leading up to it, I had done a lot of thinking about what was coming. One of the things I reached for was Norbert Elias’s book, The Loneliness of the Dying. I had come to know Elias’s work through my research on the history of violence and crime, and it had come to play an important role in my thinking about the world. I suppose it might strike you as odd to consult a sociological theorist when dealing with a personal sorrow; on the other hand, maybe it is a sign of quality theory that it tells you something useful about real life.

In any case, The Loneliness of the Dying is quite a remarkable little book. It betrays, in parts, Elias’s tendency to express himself in a somewhat dry, sociological language, but there are other insightful and almost poetic passages.

I quoted one last year:

Death is not terrible. One passes into dreaming and the world vanishes -- if all goes well. Terrible can be the pain of the dying, terrible, too, the loss of the living when a beloved person dies. There is no known cure. We are part of each other. [...]

There are indeed many terrors that surround dying. What people can do to secure for each other easy and peaceful ways of dying has yet to be discovered. The friendship of those who live on, the feeling of dying people that they do not embarrass the living, is certainly part of it. And social repression, the veil of unease that frequently surrounds the whole sphere of dying in our days, is of little help to people. Perhaps we ought to speak more openly and clearly about death, even if it is by ceasing to present it as a mystery. Death hides no secret. It opens no door. It is the end of a person. What survives is what he or she has given to other people, what stays in their memory. If humanity disappears, everything that any human being has ever done, everything for which people have lived and fought each other, including all secular or supernatural systems of belief, becomes meaningless.

(The Loneliness of the Dying, trans. Edmund Jephcott, 1985, pp. 66 and 67).

In the brief comments I managed at my mother's funeral, I quoted another passage. ‘Death’, Elias wrote, ‘is a problem of the living. Dead people have no problems.’

My mother was born into a poor-but-respectable family in Stanley Baldwin’s Britain, and she finished school at 14 to go to work, which was typical of a girl in her class and time and place. And despite crossing an ocean and ascending into the relatively comfortable lower reaches of the post-war American middle class, she remained indelibly marked by those origins, which only seemed to emerge more and more during the last decade and a half of her life.

One might think it odd, then, to remember her with words borrowed from an academic, the founder of figurational sociology – and a German no less. (Albeit one who was a victim of the Nazis and eventually became a British citizen.)

However, I was pleased to find that the words I had groped for turned out not merely to be the unfortunate affectation of a son with Too Much Education: in talking to the woman who had supervised my mother’s hospice care, I discovered that Elias’s book – with its condemnation of the ‘veil of unease’ modern society had thrown around death and the resulting isolation of the dying that this caused – had been one of the works that had inspired her to do what she was doing.

And what she and her colleagues were doing was impressive indeed. Like my mother, my father (two decades earlier) had died at home, cared for by my mother with the assistance of hospice.

Watching the relentless approach of his death over 18 months had made a strong impression on my teenage brain, as you might guess. In any case, since I came late in my parents’ lives – they were in their mid-40s when I surprisingly arrived on the scene – this meant that by the time I was in high school many of their friends (the adults I was closest to) were in their 60s or older, and the usual attrition was already well under way. By the time I graduated, I had carried the coffins of some half a dozen people whom I had loved very much.

What I suppose I’m trying to say is that, fairly early on, it had become clear to me that death was a fairly normal part of life.

(I have no wish to exaggerate my experience: obviously, violent death is something I’ve no direct experience of, something that far too many young people in far too many parts of the world have to deal with. I am not comparing myself to them.)

In any case, I had to think about a lot of the above a couple of weeks ago, when I visited a remarkable exhibition at the Wellcome Collection in London.

In ‘Life Before Death’, German photographer Walter Schels offers a powerful meditation on the experiences of dying people. Schels contacted people at hospices and found several who were willing to be photographed shortly before and immediately after their deaths. The result is a series of portraits combined with stories (written by Schels’s partner Beata Lakotta) that – I think – express in a manner that is all too rare the curious mixture of profundity and banality that inheres in the experience of death.

In their low-key way, they manage to pull back the veil, at least a little bit, on the mysteries of the dying.

Joanna Moorhead’s profile of Schels and Lakotta for the Guardian makes clear what an emotional and logistical challenge this kind of project posed. Schels was motivated by his own fears regarding mortality (and his comments about his early life demonstrate that early exposure to death doesn’t necessarily inure one to its terrors). The essay also points out something that echoes Elias’s words that I quoted above:

But, horrifying though photographing the bodies was, more shocking still for Schels and Lakotta was the sense of loneliness and isolation they discovered in their subjects during the before-death shoots. "Of course we got to know these people because we visited them in the hospices and we talked about our project, and they talked to us about their lives and about how they felt about dying," explains Lakotta. "And what we realised was how alone they almost always were. They had friends and relatives, but those friends and relatives were increasingly distant from them because they were refusing to engage with the reality of the situation. So they'd come in and visit, but they'd talk about how their loved one would soon be feeling better, or how they'd be home soon, or how they'd be back at work in no time. And the dying people were saying to us that this made them feel not only isolated, but also hurt. They felt they were unconnected to the people they most wanted to feel close to, because these people refused to acknowledge the fact that they were dying, and that the end was near."

They both feel altered by their work on the project:

Both Schels and Lakotta feel the experience of being close to so many dying people has changed how they feel not only about dying themselves, but how they feel about living - and also, how they would support a friend or relative through terminal illness. "I know now how important it is to be there, or at least to offer to be there, as much as possible - and to not be afraid of asking questions, and of listening to the answers," says Lakotta.She’s absolutely right. It doesn’t make death any less real or painful, of course. Here we reach, as in so many cases, the limits of discourse. But the end of life is one of those times where small gestures and simple honesty can have an enormous value.

Over the last few years of her life, my mother and I spoke quite openly about death. We had some different views on the matter of the afterlife, but, once acknowledged, that mattered far less than you might think. (As Moorhead observes of Schels, ‘He remains, as he has long been, an agnostic, having noticed that believers and non-believers alike showed the same fear of the unknown that awaited them.’)

Although no stranger to self-dramatisation, she faced her end with a clear-eyed stoicism that was remarkable. Don’t misunderstand: she was terrified. But somehow she managed to exude both calmness and a dark sense of humour almost to the end. And then there followed an awful period in which she could no longer express anything coherently. There were occasional moments of lucidity and recognition in her eyes. What was going on behind them, though, remains a mystery. The peaceful expression that, eventually, marked the end of her struggle is difficult to describe in words. But I believe I recognised it in many of the images that Schels captured.

The exhibit runs to 18 May. For those in London, I recommend that you go. Leave yourself some time. This is not something to rush through. Spend a good long time looking at the faces. And read all of their stories.

It is unsettling and saddening and uncomfortable. But it also generates, in the end, a curious sense of hushed tranquillity. (A similar set of emotions, I note, that accompanied my reading of Jim Crace’s powerful novel, Being Dead. Something, as The Wife has pointed out, that is rather more complicated than 'joy'.)

If you’re not in London, a sample of the images is available.

This has become far longer than I intended, so I'll conclude by leaving the last word to Schels (and by thanking him and Lakotta for their powerful work):

"What I was used to," says Schels, who has taken hundreds of portraits during his career, "was people who smiled for the camera. It's usually an automatic response. But these people never smiled. They were incredibly serious; and more than that, they weren't pretending anything any more. People are almost always pretending something, but these people had lost that need. I felt it enabled me as a photographer to get as close as it's possible to get to the core of a person; when you're facing the end, everything that's not real is stripped away. You're the most real you'll ever be, more real than you've ever been before".

Breakfast Exercise

"The press photograph is a message", Roland Barthes wrote in 1961 (in his essay "The Photographic Image"). In his view, this message consists of two meanings, the denotative meaning (i.e. that representing the world, "literal reality" - the analogon) and the connotative meaning (i.e. that expressing the photographer's take on the motif as well as, possibly, social attitudes and prejudices). While the former is a message without a code, the latter is thoroughly encoded, thereby representing "the manner in which the society to a certain extent communicates what it thinks of it [i.e. the topic]." This leads to what Barthes calls "the photographic paradox" (that a coded message is based on a message without a code) ... but let's not go into that.

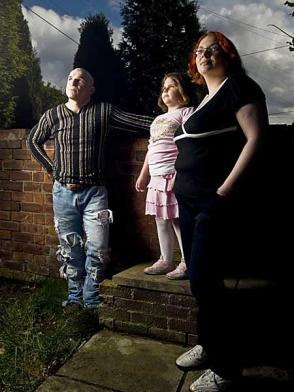

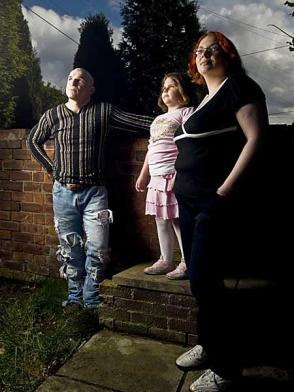

Rather, let us all together apply Barthes' distinction between denotation and connotation to this photograph from yesterday's Independent, accompanying an article entitled: "The brain drain: What if all the Poles went home?" (a good, reasonable, liberal piece defending the fundamental worthiness of all those eastern European labourers without whom little Britain could not be):

Whatever basic, uncoded message we might find in this picture ("three people al fresco"), it is completely submerged by its social encoding - this picture is an obvious piece of unflattering propaganda. As in Pre-Raphaelite photo-realism, each and every detail in this picture is heavily symbolic - from the careful arrangement of the three bodies, to the mossy slabs on which they stand, to the dramatic skies: ordinariness rendered outstanding by the photographer's attentive, arty eye. This little group is a sign of our troubled times of intolerance and xenophobia, where brave reporters from the Independent, like knights in shining armour, come to the aid of the downtrodden victims of the British tabloid press.

But don't they also look a little like a cross between Romero's living dead (or suchlike horror fare: especially the sturdy little girl, who resembles the zombie children in the 1950s movie where all the kids in a little town are possessed ... can someone remind me of the title, please?*) and the kind of eerie creatures that people the illustrations of the Jehovah's Witnesses' Watchtower? Looking ahead and up (but also outside of the picture), benevolently smiling - possibly already aware of a promised land somewhere else, where they can do their plumbing and laundering and toilet cleaning in peace.

That's what those eager, benevolent Polish faces are saying (whom the hypocritical article asks us - not? - to love): "Please, please let us clean toilets in peace!"

And the image responds: "Yes, but not here. And would you please turn off the lights before you leave."

[UPDATE] Someone did remind me! Thanks to Ario I now know that I was thinking of Wolf Rilla's Village of the Damned (1960).

Kind of apt, I believe.

Rather, let us all together apply Barthes' distinction between denotation and connotation to this photograph from yesterday's Independent, accompanying an article entitled: "The brain drain: What if all the Poles went home?" (a good, reasonable, liberal piece defending the fundamental worthiness of all those eastern European labourers without whom little Britain could not be):

Whatever basic, uncoded message we might find in this picture ("three people al fresco"), it is completely submerged by its social encoding - this picture is an obvious piece of unflattering propaganda. As in Pre-Raphaelite photo-realism, each and every detail in this picture is heavily symbolic - from the careful arrangement of the three bodies, to the mossy slabs on which they stand, to the dramatic skies: ordinariness rendered outstanding by the photographer's attentive, arty eye. This little group is a sign of our troubled times of intolerance and xenophobia, where brave reporters from the Independent, like knights in shining armour, come to the aid of the downtrodden victims of the British tabloid press.

But don't they also look a little like a cross between Romero's living dead (or suchlike horror fare: especially the sturdy little girl, who resembles the zombie children in the 1950s movie where all the kids in a little town are possessed ... can someone remind me of the title, please?*) and the kind of eerie creatures that people the illustrations of the Jehovah's Witnesses' Watchtower? Looking ahead and up (but also outside of the picture), benevolently smiling - possibly already aware of a promised land somewhere else, where they can do their plumbing and laundering and toilet cleaning in peace.

That's what those eager, benevolent Polish faces are saying (whom the hypocritical article asks us - not? - to love): "Please, please let us clean toilets in peace!"

And the image responds: "Yes, but not here. And would you please turn off the lights before you leave."

[UPDATE] Someone did remind me! Thanks to Ario I now know that I was thinking of Wolf Rilla's Village of the Damned (1960).

Kind of apt, I believe.

Tuesday, April 29, 2008

(The) truth and (its) consequences

Ah....the solution to my find-a-publisher problem is becoming so clear to me now. It's so simple: make shit up! (Thanks to The Wife for the link)

The publication of a biography of Louis XIV has now been held up because one of its primary sources was not exactly...er,...primary.

To be fair, of course, in writing non-fiction there is always the danger of making factual mistakes (a recurring nightmare here), and the author in question seems to have been merely(!) sloppy rather than devious.

Still, I would agree with at least the general drift of this:

While we're on the topic of facts -- and before I get back to trying to flog my humble little manuscript (a cross, of sorts, between biography and cultural history, with lots of old-school endnotes and the like) -- let us enjoy a little interlude on black-cab epistemology:

The publication of a biography of Louis XIV has now been held up because one of its primary sources was not exactly...er,...primary.

To be fair, of course, in writing non-fiction there is always the danger of making factual mistakes (a recurring nightmare here), and the author in question seems to have been merely(!) sloppy rather than devious.

Still, I would agree with at least the general drift of this:

"Thirty years ago this never would have happened. Then, people who wrote biographies were trained in how to carry out archival research. The same cannot be said of Veronica Buckley or many others like her," said Jerry Brotton, professor of Renaissance studies at Queen Mary, University of London. "There is a whole industry now around historical biographies. Publishers know that they sell, but at the same time they will knock back book proposals unless an author promises something really racy."Brotton was a lone voice of dissent on Buckley's first book, which he criticised in the New Statesman for "anachronistic, novelistic speculation in place of genuine historical detail" and relying on "outdated and unreliable historical sources".

"I've been reviewing these sort of books endlessly for a few years now, and they're getting worse," he commented. "One the other day was filled with "might haves" and "could haves"; by the time you would get to the end of a chapter all of a sudden these coulds and mights had been turned into facts."

While we're on the topic of facts -- and before I get back to trying to flog my humble little manuscript (a cross, of sorts, between biography and cultural history, with lots of old-school endnotes and the like) -- let us enjoy a little interlude on black-cab epistemology:

(Stewart Lee, via Geoff)

Monday, April 28, 2008

Words and Music

Are there fans of The Notwist out there? If so, here's some reading matter!

And here's some music to accompany it:

And here's some music to accompany it:

Saturday, April 26, 2008

As the Humph put it...

Already mentioned here once.

"As we journey through life, discarding baggage along the way, we should keep an iron grip, to the very end, on the capacity for silliness. It preserves the soul from dessication."

Absolutely.

We -- both of us -- agree.

Stay silly, people.

"As we journey through life, discarding baggage along the way, we should keep an iron grip, to the very end, on the capacity for silliness. It preserves the soul from dessication."

Absolutely.

We -- both of us -- agree.

Stay silly, people.

Getting tired of that shit.

Via Terry Glavin.

As someone who is in favour of more bicycle paths and fewer plastic bags, I still find this to be both hysterical and meaningful.

Dig it!

As someone who is in favour of more bicycle paths and fewer plastic bags, I still find this to be both hysterical and meaningful.

Dig it!

Read before you type. Please. No, really.

Over the last week or so, it so happens that I've been having an interesting e-mail discussion with a recently made friend that has involved evolution, human behaviour, Richard Dawkins, 'spirituality', the possibility of 'group selection' and related topics. It has become clear that we have different perspectives on these various issues, however -- as in all high-quality discussions amongst people with varying viewpoints -- I feel as if it's been a worthwhile use of my time and that I've actually learned something. Or, at least, when we finally differ, I continue to maintain my full respect toward the person with whom I disagree. It has, in fact, been a pleasure to exchange viewpoints.

It's not very easy to define, but I have had precisely the opposite feeling after reading an article by Pat Shipman, a 'professor of biological anthropology', published in the New York Sun. (Via A&L Daily)

Dr. Shipman, it is quite clear, does not like Richard Dawkins's book, The Selfish Gene.

Unfortunately, she shows no sign of having actually read it.

(I know: this is an accusation that appears rather often at this blog; however, I must say that it so frequently seems apposite that I can't help but make it. I would be pleased to receive any evidence to the contrary. Believe me, I would.)

In fact, she seems to dislike Dawkins so much that she can't bring herself to refer to him by his title. Dawkins has a D.Phil and a D.Sc., which in many places would lead to him being called 'Dr.' She denies him this privilege, referring throughout her article to 'Mr. Dawkins'. This might be acceptable in some contexts -- I mean, I don't always insist on my own title-- however, on her departmental website, she prefers being referred to by her title.

Fair is fair, Dr. Shipman. Thus, your insistent repetition of 'Mr.' seems in some way dismissive.

Anyway, in her brief, crappy article 'Reconsiderations: Richard Dawkins and His Selfish Meme', Dr. Shipman essentially argues that Dawkins's book is not only wrong-headed but has actually has had a malevolent effect on science and human morality.

However, it is actually her own ridiculous analysis of Dawkins's book that proves to be laughable.

The hilarity begins on the first page of her article, where she claims:

This is, not to mince words, utter nonsense.

The word 'selfish' has led to all kinds of misunderstandings of Dawkins's theory, but he has explained at length (including in The Selfish Gene itself) that the metaphor he chose to describe gene-level 'motives' did not require relentless selfishness on the level of individual behaviour. In the thirty years since his book's publication, he has taken ample opportunity to try to correct this misunderstanding. (Beyond even the clarifications in the book itself.)

But even as explained in the first few pages of the original edition of The Selfish Gene, Dawkins made clear that he was interested in the origins of altruism. Even more in the revised version (with a couple of extra chapters emphasising even further the theme of altruism), Dawkins illustrates repeatedly -- how could Dr. Shipman have missed this?! -- how simple ruthlessness does not pay off in most evolutionary stakes and how some degree of altruism (at least that oriented toward kin- or based on reciprocity) does.

Does the phrase 'tit-for-tat' ring a bell, Dr. Shipman? If you have even a glancing familiarity with Dawkins's work, then it should.

If not, then, please, hold your tongue until you have done some required reading. Such as, say, the book you're pontificating about in the New York Sun. At least that should be on your required reading list.

Because Dawkins -- even in the book that Shipman critiques but doesn't seem to have read -- dealt with this issue quite clearly:

Dr. Shipman might not like this latter conclusion (the 'limitations' bit), but to argue that Dawkins ignored altruism is wrong, wrong, wrong.

In the revised version of The Selfish Gene that I own (the 1989 Oxford edition) there are even further chapters discussing the topic of altruism.

Moreover, considering the flippancy with which she refers to 'lumbering robots' and 'survival machines' on the first page of her misbegotten screed, you might think that Dawkins never considered the difference between genes and beings with more subtlety.

However, in The Selfish Gene (yeah, the book that Shipman, you'd have thought, had read), he observed,

In contrast to Dawkins's view, Dr. Shipman advocates a recent article by E.O. Wilson and D.S. Wilson that has sought to revive a notion of 'group selection'.

Now, I am a great admirer of E.O. Wilson for many reasons (his book Consilience is one that I would recommend to anyone interested in unifying the humanities with the natural sciences and his environmental advocacy has been consistently inspiring...moreover, he manages to impart the way that ants are endlessly fascinating. Who'd have thought that possible?), though I'm rather more sceptical about the other (non-related) Wilson.

In any case, I'm not sure that Dr. Shipman has done much to benefit group selectionism, as she seems to think that this simply means 'the good of the species' (her article, page 1).

Even advocates of group selection (or, more accurately, multi-level selection) are careful enough to emphasise a more nuanced version of the theory.

However, here again, Dr. Shipman lets provides yet another embarrassing howler. Speaking of Wilson and Wilson, she states,

Having (apparently) not read The Selfish Gene, she is clearly unaware both 'kin selection' and 'reciprocal altruism' are central features of Dawkins's book. (See, particularly, Chapter 6, 'Genesmanship', for the former and Chapter 10, 'You scratch my back, I'll ride on yours' for the latter.)

Indeed, Dr. Shipman appears to present 'kin selection' as somehow in opposition to Dawkins's work, whereas Dawkins very much saw himself as popularising the work of Bill Hamilton, who put the notion of kin selection on a more stable mathematical footing.

For all her blathering on about kin-selection and the altruistic behaviour of meerkats, Dr. Shipman overlooks the fact that Dawkins -- in his revised 1989 edition of The Selfish Gene -- discussed the altruistic behaviour of vampire bats.

In conclusion: to suggest that 'selfish' genes invariably mean 'selfish' behaviour is to fundamentally misunderstand Dawkins's book.

For a professor of 'biological anthropology' managing to avoid that simple error should be a doddle; however, Dr. Shipman appears to not be up to the challenge. She should be ashamed of herself.

Not only does she present the theories of John Maynard Smith as somehow opposed to those of Dawkins (who makes extensive use, for instance, of his notion of the Evolutionarily Stable Strategy), but she oddly lumps kin and group selection together, as if Dawkins had not made abundant arguments in favour of the former.

One of the crowning insults of Shipman's little package of intellectual trash is to claim that Dawkins has in some way assisted the spread of the 'Intelligent Design' movement:

What?!

Shipman doesn't even begin to explain what she means by this, and she should be deeply ashamed of linking Dawkins's work with any presumed success of 'Intelligent Design', a movement that Dawkins has been intensely focused on combating.

She even has the gall to argue that the book has provoked a 'backlash against science'.

I don't know much about the work of Dr. Pat Shipman, and for all I know she writes brilliantly and insigtfully within her own field. But having examined this piece of intellectual nothingness alongside her depthless article on violence in the wake of September 11th, I have to say this: I'm not impressed.

She definitely has some more reading to do. And in the meantime, she should keep her mouth shut.

And, I suggest, she should refrain from using the word 'biological' in her title until she demonstrates that she has the ability to read, understand and recapitulate works on that topic.

And, for what it's worth, A&L Daily should take a bit more care in the articles that it recommends.

It's not very easy to define, but I have had precisely the opposite feeling after reading an article by Pat Shipman, a 'professor of biological anthropology', published in the New York Sun. (Via A&L Daily)

Dr. Shipman, it is quite clear, does not like Richard Dawkins's book, The Selfish Gene.

Unfortunately, she shows no sign of having actually read it.

(I know: this is an accusation that appears rather often at this blog; however, I must say that it so frequently seems apposite that I can't help but make it. I would be pleased to receive any evidence to the contrary. Believe me, I would.)

In fact, she seems to dislike Dawkins so much that she can't bring herself to refer to him by his title. Dawkins has a D.Phil and a D.Sc., which in many places would lead to him being called 'Dr.' She denies him this privilege, referring throughout her article to 'Mr. Dawkins'. This might be acceptable in some contexts -- I mean, I don't always insist on my own title-- however, on her departmental website, she prefers being referred to by her title.

Fair is fair, Dr. Shipman. Thus, your insistent repetition of 'Mr.' seems in some way dismissive.

Anyway, in her brief, crappy article 'Reconsiderations: Richard Dawkins and His Selfish Meme', Dr. Shipman essentially argues that Dawkins's book is not only wrong-headed but has actually has had a malevolent effect on science and human morality.

However, it is actually her own ridiculous analysis of Dawkins's book that proves to be laughable.

The hilarity begins on the first page of her article, where she claims:

In Mr. Dawkins's view, the organisms containing those genes are merely "lumbering robots" or "survival machines" that house and carry genetic information. The implication is that, in these terms, selfishness, even ruthless selfishness, pays off, and altruism does not.

This is, not to mince words, utter nonsense.

The word 'selfish' has led to all kinds of misunderstandings of Dawkins's theory, but he has explained at length (including in The Selfish Gene itself) that the metaphor he chose to describe gene-level 'motives' did not require relentless selfishness on the level of individual behaviour. In the thirty years since his book's publication, he has taken ample opportunity to try to correct this misunderstanding. (Beyond even the clarifications in the book itself.)

But even as explained in the first few pages of the original edition of The Selfish Gene, Dawkins made clear that he was interested in the origins of altruism. Even more in the revised version (with a couple of extra chapters emphasising even further the theme of altruism), Dawkins illustrates repeatedly -- how could Dr. Shipman have missed this?! -- how simple ruthlessness does not pay off in most evolutionary stakes and how some degree of altruism (at least that oriented toward kin- or based on reciprocity) does.

Does the phrase 'tit-for-tat' ring a bell, Dr. Shipman? If you have even a glancing familiarity with Dawkins's work, then it should.

If not, then, please, hold your tongue until you have done some required reading. Such as, say, the book you're pontificating about in the New York Sun. At least that should be on your required reading list.

Because Dawkins -- even in the book that Shipman critiques but doesn't seem to have read -- dealt with this issue quite clearly:

The argument of this book is that we, and all other animals, are machines created by our genes. Like successful Chicago gangsters, our genes have survived, in some cases for millions of years, in a highly competitive world. This entitles us to expect certain qualities in our genes. I shall argue that a predominant quality to be expected in a successful gene is ruthless selfishness. This gene selfishness will usually give rise to selfishness in individual behavior. However, as we shall see, there are special circumstances in which a gene can achieve its own selfish goals best by fostering a limited form of altruism at the level of individual animals. 'Special' and 'limited' are important words in the last sentence. Much as we might wish to believe otherwise, universal love and the welfare of the species as a whole are concepts that simply do not make evolutionary sense. (p. 2, emphasis added)

Dr. Shipman might not like this latter conclusion (the 'limitations' bit), but to argue that Dawkins ignored altruism is wrong, wrong, wrong.

In the revised version of The Selfish Gene that I own (the 1989 Oxford edition) there are even further chapters discussing the topic of altruism.

Moreover, considering the flippancy with which she refers to 'lumbering robots' and 'survival machines' on the first page of her misbegotten screed, you might think that Dawkins never considered the difference between genes and beings with more subtlety.

However, in The Selfish Gene (yeah, the book that Shipman, you'd have thought, had read), he observed,

Some people object to what they see as an excessively gene-centred view of evolution. After all, they argue, it is whole individuals with all their genes who actually live or die. I hope I have said enough in this chapter [Chapter 3, 'Immortal coils', and, indeed, he did] to show that there is really no disagreement here. Just as whole boats win or lose races, it is indeed individuals who live or die, and the immediate manifestation of natural selection is nearly always at the individual level. But the long-term consequences of non-random individual death and reproductive success are manifested in the form of changing gene frequencies in the gene pool. (p. 45)Didn't you manage to read as far as page 45, Dr. Shipman?

In contrast to Dawkins's view, Dr. Shipman advocates a recent article by E.O. Wilson and D.S. Wilson that has sought to revive a notion of 'group selection'.

Now, I am a great admirer of E.O. Wilson for many reasons (his book Consilience is one that I would recommend to anyone interested in unifying the humanities with the natural sciences and his environmental advocacy has been consistently inspiring...moreover, he manages to impart the way that ants are endlessly fascinating. Who'd have thought that possible?), though I'm rather more sceptical about the other (non-related) Wilson.

In any case, I'm not sure that Dr. Shipman has done much to benefit group selectionism, as she seems to think that this simply means 'the good of the species' (her article, page 1).

Even advocates of group selection (or, more accurately, multi-level selection) are careful enough to emphasise a more nuanced version of the theory.

However, here again, Dr. Shipman lets provides yet another embarrassing howler. Speaking of Wilson and Wilson, she states,

The pair asserted persuasively that altruism and cooperation can be adaptive if they are directed toward relatives who share a suite of one's genes (kin selection) or if relationships can be established within a group in which cooperation is rewarded with future reciprocity.

Having (apparently) not read The Selfish Gene, she is clearly unaware both 'kin selection' and 'reciprocal altruism' are central features of Dawkins's book. (See, particularly, Chapter 6, 'Genesmanship', for the former and Chapter 10, 'You scratch my back, I'll ride on yours' for the latter.)

Indeed, Dr. Shipman appears to present 'kin selection' as somehow in opposition to Dawkins's work, whereas Dawkins very much saw himself as popularising the work of Bill Hamilton, who put the notion of kin selection on a more stable mathematical footing.

For all her blathering on about kin-selection and the altruistic behaviour of meerkats, Dr. Shipman overlooks the fact that Dawkins -- in his revised 1989 edition of The Selfish Gene -- discussed the altruistic behaviour of vampire bats.

In conclusion: to suggest that 'selfish' genes invariably mean 'selfish' behaviour is to fundamentally misunderstand Dawkins's book.

For a professor of 'biological anthropology' managing to avoid that simple error should be a doddle; however, Dr. Shipman appears to not be up to the challenge. She should be ashamed of herself.

Not only does she present the theories of John Maynard Smith as somehow opposed to those of Dawkins (who makes extensive use, for instance, of his notion of the Evolutionarily Stable Strategy), but she oddly lumps kin and group selection together, as if Dawkins had not made abundant arguments in favour of the former.

One of the crowning insults of Shipman's little package of intellectual trash is to claim that Dawkins has in some way assisted the spread of the 'Intelligent Design' movement:

The picture of evolution offered by [The Selfish Gene], and others by Mr. Dawkins, which many found bleak, also contributed to the growth and stridency of the intelligent design movement to undercut the teaching of evolution in public schools.

What?!

Shipman doesn't even begin to explain what she means by this, and she should be deeply ashamed of linking Dawkins's work with any presumed success of 'Intelligent Design', a movement that Dawkins has been intensely focused on combating.

She even has the gall to argue that the book has provoked a 'backlash against science'.

I don't know much about the work of Dr. Pat Shipman, and for all I know she writes brilliantly and insigtfully within her own field. But having examined this piece of intellectual nothingness alongside her depthless article on violence in the wake of September 11th, I have to say this: I'm not impressed.

She definitely has some more reading to do. And in the meantime, she should keep her mouth shut.

And, I suggest, she should refrain from using the word 'biological' in her title until she demonstrates that she has the ability to read, understand and recapitulate works on that topic.

And, for what it's worth, A&L Daily should take a bit more care in the articles that it recommends.

R.I.P. Humphrey

This is sad: Humphrey Lyttleton, host of Radio 4's "I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue" has died. I really liked that show and know that somewhere in the depths of one of the many boxes in the basement that have survived several changes of address unopened I have a bunch of tapes (tapes!) with recordings of "I'm Sorry ..." from the 1990s. In fact, I think I have a CD of Lyttleton and his band somewhere.

I know, I know, I'm an old-fashioned girl at heart ....

Guardian obit. here.

I know, I know, I'm an old-fashioned girl at heart ....

Guardian obit. here.

Friday, April 25, 2008

Forbidden books?

Süddeutsche Zeitung reports that the Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland (Central Council of Jews in Germany) defends the idea -- put forward by the Dokumentationszentrum Reichsparteitagsgelände in Nuremberg -- of an annotated critical edition of Hitler's Mein Kampf. It seems a pity that the Free State of Bavaria, the copyright holder (no, I wasn't aware of that either), resists what appears to be a timely project of pulling the rug out from under this shitty piece of propaganda and combating its ongoing mystification (in certain ... "circles") and potential misuse once copyright runs out in 2015.

The new edition would be provided by the respectable Institut für Zeitgeschichte in Munich. The Bavarian government, however, claims that such a publication would violate the memory and respect of victims of the Holocaust, thereby potentially betraying those it seeks to defend. Not a good idea, given recent figures revealing that Bavaria has, over the past years, become something of a neo-Nazi stronghold.

The new edition would be provided by the respectable Institut für Zeitgeschichte in Munich. The Bavarian government, however, claims that such a publication would violate the memory and respect of victims of the Holocaust, thereby potentially betraying those it seeks to defend. Not a good idea, given recent figures revealing that Bavaria has, over the past years, become something of a neo-Nazi stronghold.

Nature (Black) Watch

Before I'm off to my afternoon shift at the desk, a brief silly interlude: Russian Mutant Killer Squirrels hauting the Cambridgeshire countryside and hunting down "their grey cousins."

If you can't be bothered to read the article in its complex totality, here's my favourite bit (clearly based on the author's recent viewing of 28 Days Later):

Note how the article does not even bother to mention that the poor little grey victims of these ruthless post cold war killers (which probably all go by the name of "Vladimir") are themselves not exactly innocent. After all, these highly reproductive (and apparently very meaty) Yank critters -- cutely disneyesque though they may appear, with their little tuftless ears and biiiiig eyes -- are responsible for the long standing squirrelcide that has all but driven the indigenous red type from its natural habitats in Britain.

If you can't be bothered to read the article in its complex totality, here's my favourite bit (clearly based on the author's recent viewing of 28 Days Later):

Three years ago, a pack of Russian black squirrels bit to death a stray dog in a Russian park. They were said to have scampered off at the sight of humans, some carrying pieces of flesh.Gory!

Note how the article does not even bother to mention that the poor little grey victims of these ruthless post cold war killers (which probably all go by the name of "Vladimir") are themselves not exactly innocent. After all, these highly reproductive (and apparently very meaty) Yank critters -- cutely disneyesque though they may appear, with their little tuftless ears and biiiiig eyes -- are responsible for the long standing squirrelcide that has all but driven the indigenous red type from its natural habitats in Britain.

Thursday, April 24, 2008

Don't fence me in. At least not with that kind of fence.

I'd like to follow up on The Wife’s critique of Jürgen Habermas’s abstract pronouncements on religion and secularism to comment on a related matter.

In one of the summaries of Habermas’s paper (full version -- in rather heavy-duty philosophical German -- here), part of his argument is presented like this:

He has attested to a 'truth potential' ('Wahrheitspotenzial') in religion, one to which even secular citizens should attend.

Now, I’m not exactly sure what Habermas means by this, but I detected echoes of this notion in a couple of other recent commentaries, both of which seem to be based on the notion that there is a specifically religious truth that can -- to borrow from Habermas -- be 'translated' to have meaning for the secular world.

In particular, they both focus on 'limits' to human knowledge and action.

While I would not for a moment doubt that the universe -- and our own nature -- places limits on both of those things, I can't see any reason to think that there is a separate, special religious ‘truth’ on this matter.

We begin with Chris Hedges, author of I Don't Believe in Atheists.

As quoted by Ophelia Benson, Hedges argues the following:

I can’t do any better than Ophelia’s reply:

Indeed.

What is so irksome about Hedges’s comments (well, one of the things) is that his fevered imagination has conjured up a nonexistent army of New Atheist utopians. He sees them as the secular equivalent of religious fundamentalists (such an original inversion!) and claims that they are going about preaching a Darwinian gospel that has as its ultimate goal the Perfectability of Man.

Hedges, for instance, says that although atheists do not have the political influence of the religious right (again, quoted by Ophelia),

Ophelia responds:

Like Ophelia, I’ve actually read the authors that Hedges rails against. This has led me to being undecided: I'm unsure whether I have to conclude that he is deeply mendacious, pathologically delusional or simply cannot read.

There may be legitimate debates to be had, but Chris Hedges is not having them.

(A personal digression, if you will, before we continue, which follows up on Ophelia’s scathing comments on Hedges’s problems with the truth. I, too, wrote and published a book. In it, I had to document carefully all of the claims that I was making. I have also recently completed a second historical manuscript, and I have -- again -- invested an immense amount of effort in to ensure that what I was saying was not only interesting and a good read but was also well-supported and, you know, factual. It is proving, however, an upward struggle to find an agent or popular press who will even take a serious look at it, despite the fact that it contains far more sex, violence and human interest than Hedges seems to manage in his sour, leaden, humourless ravings. Still, he has the odd ability to pile up any old stack of rancid arguments with only a glancing relationship to reality and nevertheless find a publisher that can turn his book into a bestseller. Is this flawed animal maybe just a wee bit envious? You bet. Ok, back to the carefully reasoned argumentation. I thank you for your patience.)

We turn now to Georgetown political science professor, Patrick Deneen. Now, I often find Deneen to be insightful on topics such as sustainable living, the environment or the problem of resource scarcity. We also agree very much on the virtues of clotheslines. He's clearly a different quality of thinker than Chris Hedges.

However, he seems to be advocating a related (if more thoughtfully expressed) message as Hedges: we ignore the insights into the human condition provided by religion at our own peril.

In a recent post, Deneen has -- based on recent comments by Wendell Berry in Harper's and by Pope Benedict in an address to Catholic educators -- asserted the importance of recognising the limits of human freedom and knowledge.

As reported by Deneen, Berry responds to the contemporary civilisational crises by turning to literature:

Deneen links these thoughts on 'self-imposed limits' to a passage from Benedict's recent address.

Maybe it's just me, but I can't help finding something distinctly chilling in these words from the leader of the world's largest single Christian denomination:

Deneen -- who as far as I can tell apparently agrees with at least the gist of this -- favourably compares Benedict's vision of a quest for knowledge that is not 'somehow autonomous or independent' of 'the faith and the teaching of the Church' to another, more 'debased' and untrammelled version of academic freedom:

Now, readers of this blog will know that its contributors have more than a small quibble with some of the more esoteric and transcendental tendencies in the humanities. However, it would seem to me that religion and (much) post-modernist thinking share a rather paranoid resistance to science and materialism.

In this respect, the naive liberationism that Deneen detects in some humanities departments is just the other side of the same coin as the spiritual yearning to escape our physical bonds offered by religion. (In any case, given their detachment from reality, I don't imagine literature departments are going to be liberating anyone soon.)

As The Wife put it some time ago, spirituality is not the answer.

Undoubtedly, our limits as people are very real. But the assumption that we need religion to tell us this is a very strange one. The accusations made by Hedges are full-on Mad Doctor fantasies: anyone who has spent any significant time with the works of Dawkins or Dennett or Harris (just to name the most well-known of the secular villains out there) will know that all their works emphasise the natural basis (and, thus, the limits) of human beings.

Following a detailed exploration of the human mind, Steven Pinker has observed,

Just precisely where in all this can you find a vision of human perfectionism?

Many of the limits we face, of course, are beyond our bodies, and they will affect us whether we recognise them or not. Since Deneen has argued that the return of scarcity may force us to live lives more in accordance with traditional 'virtues', it is odd that he seems to overlook the reverse: that those past virtues were a product of scarcity, rather than of any external (i.e., God-given or transcendentally cultural) source. If you depend on good husbandry to make sure that you have crops next year, you will tend to find that good husbandry becomes an important -- perhaps central -- part of your culture.

Our limitations, in any case, are not dependent on our beliefs. Even were we to disbelieve in them (or do not recognise them because we are blind to our instincts) they will still shape our lives.

The world is infinitely more than what we happen to believe about it.

Finally, Deneen quotes Wendell Berry's assertion that every religious tradition he knows of 'fully acknowledg[es] our animal nature'. I find this an extraordinary re-writing of the past.

If you were to identify an institution that has resisted acknowledgement of human beings' animal nature, it would be hard to find a better one than organised religion. This is a problem, I hope it is not necessary to point out, that continues to this day. To the extent that some religious thinkers have sought to alter that view, it is because they have been forced to as a result of having to find an accommodation with well-grounded scientific findings.

Furthermore, the ‘limits’ one finds in religious views of humanity are all too often the wrong kinds of limits, deriving from an intellectually vacant alleged incapacity to fully comprehend 'God’s will 'or from the frankly unpleasant and bizarre notion of ‘original sin’. These notions do not simply point to human failings in some kind of vague and general way (i.e., we're imperfect); rather, they describe very specific flaws that have a very specific (and imaginary) origin.

At root, both Hedges and Deneen's arguments seem to contain a category error: finding answers in the Bible (or literature) for how to deal with social organisation, technology, environmental catastrophe or the impending food shortages that may (rather soon) cause misery and death in some parts of the world is about as fruitful as looking to Ulysses to tell you how to fix your car.

Nor is it the case that moderation and goodness are unquestionably inherent in religious texts, even if moderate and good people will, of course, find such meanings if they look for them.

It is striking that so many of the current arguments in favour of religious belief are reversals of so much of what religion has often meant. Throughout its history, religion has downplayed the value of our earthly existence in favour of promising us an eternal life in the hereafter. Now, we are told, we need religion to make our lives meaningful in the here and now.

We need religion to learn moderation? A glance at its history suggests that few, if any, religions have been much reluctant to expand their own power (or that of certain nations) beyond all bounds of temperance. I know several people (a few of whom I'm related to) who have no doubt that God wants them to prosper and consume and take the most crass dominion over the Earth.

We need religion to teach us about human dignity? That’s a new one: how often have religious motives been the basis for violating the dignity of whomever is perceived as an infidel? (Yes, that'd be right. Pretty often.)

Deneen thinks that Benedict's statement on academic freedom (quoted above) is based on an ‘abiding belief in the compatibility of faith and reason, and his confidence that honest and valiant exploration will yield knowledge that is ultimately compatible with faith.’

That's a nice belief. But what if it doesn’t work? What if the discovery of knowledge leads in ways contrary to faith? I don’t think we’re entirely in the dark on this question, given the long history of the faithful combating, suppressing and simply ignoring things that ‘contradict the faith and the teaching of the Church’.

These, I suggest, are precisely the kinds of limits that we don't need.

In one of the summaries of Habermas’s paper (full version -- in rather heavy-duty philosophical German -- here), part of his argument is presented like this:

Secular citizens must remain open to the possibility that even religious utterances, when translated into a secular context, can have meaning for them.

He has attested to a 'truth potential' ('Wahrheitspotenzial') in religion, one to which even secular citizens should attend.

Now, I’m not exactly sure what Habermas means by this, but I detected echoes of this notion in a couple of other recent commentaries, both of which seem to be based on the notion that there is a specifically religious truth that can -- to borrow from Habermas -- be 'translated' to have meaning for the secular world.

In particular, they both focus on 'limits' to human knowledge and action.

While I would not for a moment doubt that the universe -- and our own nature -- places limits on both of those things, I can't see any reason to think that there is a separate, special religious ‘truth’ on this matter.

We begin with Chris Hedges, author of I Don't Believe in Atheists.

As quoted by Ophelia Benson, Hedges argues the following:

We have nothing to fear from those who do or do not believe in God; we have much to fear from those who do not believe in sin. The concept of sin is a stark acknowledgement that we can never be omnipotent, that we are bound and limited by human flaws and self-interest.

I can’t do any better than Ophelia’s reply:

Stark, staring bullshit. Could hardly be more wrong. Obviously there is no need whatever to believe in 'sin' to be aware that we can never be omnipotent and that we are bound and limited by human flaws and self-interest. Really it's mostly non-theists who are aware of that in the most thorough way, because theists mostly believe that we will ultimately be 'redeemed' or 'atoned' in some way. The rest of us just think we are deeply flawed animals and that's all there is to it.

Indeed.

What is so irksome about Hedges’s comments (well, one of the things) is that his fevered imagination has conjured up a nonexistent army of New Atheist utopians. He sees them as the secular equivalent of religious fundamentalists (such an original inversion!) and claims that they are going about preaching a Darwinian gospel that has as its ultimate goal the Perfectability of Man.

Hedges, for instance, says that although atheists do not have the political influence of the religious right (again, quoted by Ophelia),

they do engage in the same chauvinism and call for the same violent utopianism. They sell this under secular banners. They believe, like the Christian Right, that we are moving forward to a paradise, a state of human perfection, this time made possible by human reason. (Emphasis added)

Ophelia responds:

It's very noticeable that Hedges never offers any evidence for this kind of crap (which continues for page after page, and recurs throughout the book). He repeats it ad nauseam and offers zero quotations to back it up - which is not surprising, since there aren't any, since they don't believe any such fucking thing. This is grossly irresponsible unwarranted garbage, and it's a sign of something or other that a reputable publisher failed to throw it back in his face. I don't think the Times would have let him publish this dreck in the paper - except possibly on the Op-ed page; it's somewhat shocking that a division of Simon and Schuster published it.

There's a great deal more of this kind of thing, but you get the idea. He's beside himself with rage, he makes no effort to be accurate, he considers himself entitled to make wildly exaggerated claims, he can't think, he can't read carefully, and he's overflowing with malevolence. (Which is funny in a way, because one of his chief claims is that religion is somehow necessary for or intimately connected to goodness, compassion, generosity, that kind of thing - yet he himself displays a remarkably unpleasant belligerence coupled with carelessness with the truth.)

Like Ophelia, I’ve actually read the authors that Hedges rails against. This has led me to being undecided: I'm unsure whether I have to conclude that he is deeply mendacious, pathologically delusional or simply cannot read.

There may be legitimate debates to be had, but Chris Hedges is not having them.

(A personal digression, if you will, before we continue, which follows up on Ophelia’s scathing comments on Hedges’s problems with the truth. I, too, wrote and published a book. In it, I had to document carefully all of the claims that I was making. I have also recently completed a second historical manuscript, and I have -- again -- invested an immense amount of effort in to ensure that what I was saying was not only interesting and a good read but was also well-supported and, you know, factual. It is proving, however, an upward struggle to find an agent or popular press who will even take a serious look at it, despite the fact that it contains far more sex, violence and human interest than Hedges seems to manage in his sour, leaden, humourless ravings. Still, he has the odd ability to pile up any old stack of rancid arguments with only a glancing relationship to reality and nevertheless find a publisher that can turn his book into a bestseller. Is this flawed animal maybe just a wee bit envious? You bet. Ok, back to the carefully reasoned argumentation. I thank you for your patience.)

We turn now to Georgetown political science professor, Patrick Deneen. Now, I often find Deneen to be insightful on topics such as sustainable living, the environment or the problem of resource scarcity. We also agree very much on the virtues of clotheslines. He's clearly a different quality of thinker than Chris Hedges.

However, he seems to be advocating a related (if more thoughtfully expressed) message as Hedges: we ignore the insights into the human condition provided by religion at our own peril.

In a recent post, Deneen has -- based on recent comments by Wendell Berry in Harper's and by Pope Benedict in an address to Catholic educators -- asserted the importance of recognising the limits of human freedom and knowledge.

As reported by Deneen, Berry responds to the contemporary civilisational crises by turning to literature:

Berry's main argument is to point to the literary tradition - naming Marlowe and Milton, but drawing on Dante and including Goethe - of depicting Hell as a place without limits or boundaries. Hell is a place where bounds are not known, where judgment has been abandoned and where, because appetite roams free and wild, its denizens are enslaved to desire. We have made our own hell, largely because we have discarded the self-imposed limits of traditional human understanding, whether derived from religious, literary, or other cultural sources.

Deneen links these thoughts on 'self-imposed limits' to a passage from Benedict's recent address.

Maybe it's just me, but I can't help finding something distinctly chilling in these words from the leader of the world's largest single Christian denomination:

"In regard to faculty members at Catholic colleges universities, I wish to reaffirm the great value of academic freedom. In virtue of this freedom you are called to search for the truth wherever careful analysis of evidence leads you. Yet it is also the case that any appeal to the principle of academic freedom in order to justify positions that contradict the faith and the teaching of the Church would obstruct or even betray the university's identity and mission; a mission at the heart of the Church's munus docendi and not somehow autonomous or independent of it." (Emphasis added.)

Deneen -- who as far as I can tell apparently agrees with at least the gist of this -- favourably compares Benedict's vision of a quest for knowledge that is not 'somehow autonomous or independent' of 'the faith and the teaching of the Church' to another, more 'debased' and untrammelled version of academic freedom:

Disciplines (note the word) that were to teach us how to be human - most centrally, how to limit ourselves and our appetites, how to govern ourselves as individuals and as members of polities - have been transformed into "liberative" studies. No discipline has fallen further from its original role as a discipline and into a "liberation movement" than English literature - and it generally doesn't matter if one attends a secular or a Catholic university.

Now, readers of this blog will know that its contributors have more than a small quibble with some of the more esoteric and transcendental tendencies in the humanities. However, it would seem to me that religion and (much) post-modernist thinking share a rather paranoid resistance to science and materialism.

In this respect, the naive liberationism that Deneen detects in some humanities departments is just the other side of the same coin as the spiritual yearning to escape our physical bonds offered by religion. (In any case, given their detachment from reality, I don't imagine literature departments are going to be liberating anyone soon.)

As The Wife put it some time ago, spirituality is not the answer.

Undoubtedly, our limits as people are very real. But the assumption that we need religion to tell us this is a very strange one. The accusations made by Hedges are full-on Mad Doctor fantasies: anyone who has spent any significant time with the works of Dawkins or Dennett or Harris (just to name the most well-known of the secular villains out there) will know that all their works emphasise the natural basis (and, thus, the limits) of human beings.

Following a detailed exploration of the human mind, Steven Pinker has observed,

Our thoroughgoing perplexity about the enigmas of consciousness, self, will, and knowledge may come from a mismatch between the very nature of these problems and the computational apparatus that natural selection has fitted us with. (How the Mind Works, p. 565)It is something like this kind of recognition that you will find scattered throughout the works of people like Dawkins and Dennett (and many others). Evolutionary psychology is based on the notion that our minds are shaped by our animal nature with all the limits to perfection that that brings with it. (Dawkins even has a chapter in The Extended Phenotype that is called 'Constraints on Perfection'!) Christopher Hitchens uses the words 'primate' and 'mammal' throughout God Is Not Great to refer to various human beings on practically every other page.

Just precisely where in all this can you find a vision of human perfectionism?

Many of the limits we face, of course, are beyond our bodies, and they will affect us whether we recognise them or not. Since Deneen has argued that the return of scarcity may force us to live lives more in accordance with traditional 'virtues', it is odd that he seems to overlook the reverse: that those past virtues were a product of scarcity, rather than of any external (i.e., God-given or transcendentally cultural) source. If you depend on good husbandry to make sure that you have crops next year, you will tend to find that good husbandry becomes an important -- perhaps central -- part of your culture.

Our limitations, in any case, are not dependent on our beliefs. Even were we to disbelieve in them (or do not recognise them because we are blind to our instincts) they will still shape our lives.

The world is infinitely more than what we happen to believe about it.

Finally, Deneen quotes Wendell Berry's assertion that every religious tradition he knows of 'fully acknowledg[es] our animal nature'. I find this an extraordinary re-writing of the past.

If you were to identify an institution that has resisted acknowledgement of human beings' animal nature, it would be hard to find a better one than organised religion. This is a problem, I hope it is not necessary to point out, that continues to this day. To the extent that some religious thinkers have sought to alter that view, it is because they have been forced to as a result of having to find an accommodation with well-grounded scientific findings.

Furthermore, the ‘limits’ one finds in religious views of humanity are all too often the wrong kinds of limits, deriving from an intellectually vacant alleged incapacity to fully comprehend 'God’s will 'or from the frankly unpleasant and bizarre notion of ‘original sin’. These notions do not simply point to human failings in some kind of vague and general way (i.e., we're imperfect); rather, they describe very specific flaws that have a very specific (and imaginary) origin.

At root, both Hedges and Deneen's arguments seem to contain a category error: finding answers in the Bible (or literature) for how to deal with social organisation, technology, environmental catastrophe or the impending food shortages that may (rather soon) cause misery and death in some parts of the world is about as fruitful as looking to Ulysses to tell you how to fix your car.

Nor is it the case that moderation and goodness are unquestionably inherent in religious texts, even if moderate and good people will, of course, find such meanings if they look for them.

It is striking that so many of the current arguments in favour of religious belief are reversals of so much of what religion has often meant. Throughout its history, religion has downplayed the value of our earthly existence in favour of promising us an eternal life in the hereafter. Now, we are told, we need religion to make our lives meaningful in the here and now.

We need religion to learn moderation? A glance at its history suggests that few, if any, religions have been much reluctant to expand their own power (or that of certain nations) beyond all bounds of temperance. I know several people (a few of whom I'm related to) who have no doubt that God wants them to prosper and consume and take the most crass dominion over the Earth.

We need religion to teach us about human dignity? That’s a new one: how often have religious motives been the basis for violating the dignity of whomever is perceived as an infidel? (Yes, that'd be right. Pretty often.)

Deneen thinks that Benedict's statement on academic freedom (quoted above) is based on an ‘abiding belief in the compatibility of faith and reason, and his confidence that honest and valiant exploration will yield knowledge that is ultimately compatible with faith.’

That's a nice belief. But what if it doesn’t work? What if the discovery of knowledge leads in ways contrary to faith? I don’t think we’re entirely in the dark on this question, given the long history of the faithful combating, suppressing and simply ignoring things that ‘contradict the faith and the teaching of the Church’.

These, I suggest, are precisely the kinds of limits that we don't need.

Tuesday, April 22, 2008

But when worlds collide ....

Francis Sedgemore has kindly pointed us to Jürgen Habermas's recent article "Die Dialektik der Säkularisierung" and the surrounding debate in the anglophone blogosphere, which generally seems in favour of Habermas's critique of the West's belief in its own secularisation, and his suggestion that societies need to find a "balance" between the forces of secularisation and religion to solve the conflicts which haunt our globalised world.

At the risk of ruffling some feathers out there, I have to admit that I can't quite go along with the sense of agreement (whatever reservations accompany it, for instance over at normblog) with the general gist of his argument.

As a Hobbesian at heart, I've had a hard time with Habermas's naively optimistic view of humanity ("it's good to talk") for as long as I'd been trying to grapple with his difficult prose, and I've watched the veritable spiritualisation of St. Jürgen over the past several years with increasing concern (and I'm not alone, as Paolo Flores d’Arcais' much debated "Eleven Theses about Habermas" from last November reveal). As a testimony to this spiritualisation, Habermas published two books in 2005: Zwischen Naturalismus und Religion and Dialektik der Säkularisierung: Über Vernunft und Religion. The latter, it needs to be emphasised, was written together with Our Man in the Vatican.

Footnote: the Amazon.de page for the book lists Habermas, Joseph Ratzinger and Pope Benedikt XVI as authors -- an illustrious holy trinity indeed.

One of the first articles that I ever posted on this site, in which I was expressing my growing concern and confusion about an emerging academic fad for spirituality, was partly inspired by teaching chapters from Zwischen Naturalismus und Religion in a course on fundamentalism. The argument still stands, so you might as well just read the post. Needless to say, I also stand by its conclusion that it's not less rationalism that we need in this world, but more.

I suppose that Habermas's recent article might not be unrelated to these older statements, and ask forgiveness for not putting in a night shift to read "Dialektik der Säkularisierung" in its entirety; in fact, I admit that I haven't made it beyond the first page, partly because I simply have far too much to do at the moment (and Habermas is notoriously hard to read -- not the kind of fare you enjoy on returning knackered after a long day in the institution).

Suffice it to say for tonight that even the first page contains a considerable flaw that simultaneously (dialectically?) anchors and disturbs Habermas's airy (and not entirely clear) argument.

Towards the end of that page, he refers to "the visible conflicts sparked by religious issues," which in his eyes contradict our belief in the secularisation of our societies. As examples, he cites the Bishop of Canterbury's suggestion that parts of British family law should incorporate Sharia, French president Sarkozy's deployment of the police against riots in the Paris banlieue and a fire in an apartment house in Ludwigshafen, which caused the death of nine Turkish inhabitants. Initially suspected to be a racist attack, the latter turned out to have been caused by faulty wiring in the building's basement.

Forgive me for being finicky, but -- cold-hearted rationalist that I am -- I find it important to point out that only one (the first) of these examples is a clearly religious issue. The other two derive from conflicts that, strictly speaking, are socio-economic/ethnic. Since it is closer to home, I will dwell on the Ludwigshafen event, which, as far as I am aware, was never construed in religious terms (i.e. Muslims vs Christians), not even by the Turkish press, which ferociously attacked Angela Merkel, the Ludwigshafen police and fire department and Germany in general for all kinds of failings in this context.

Nevertheless, the contradiction in Habermas's opening gambit is interesting in that it affirms the sense of disconnection from reality that often characterises his work. Habermas's political philosophy always takes place in an abstract space -- that which ought to be -- removed from the real needs, motivations and urges of human beings -- that which is. In Habermas's hypothetical democratic theatre the talking is easy, communication always productive.

Schön wär's.

As part of his construction of the world as he would like it to be, Habermas, in this essay, transmutes a cultural conflict into a religious one, not only to make the point that ours is not yet a truly secular world, but also to argue that such clashes may be conducive to valuable social "learning processes."

Now, negotiation is in itself a fine and noble thing and it is cultivated even in this household. However, any conclusions reached on the basis of a false repackaging of complex cultural events as elevated theological debate seem wobbly at best.

At the risk of ruffling some feathers out there, I have to admit that I can't quite go along with the sense of agreement (whatever reservations accompany it, for instance over at normblog) with the general gist of his argument.